The Renaissance Ideal

What to strive for as a polymath

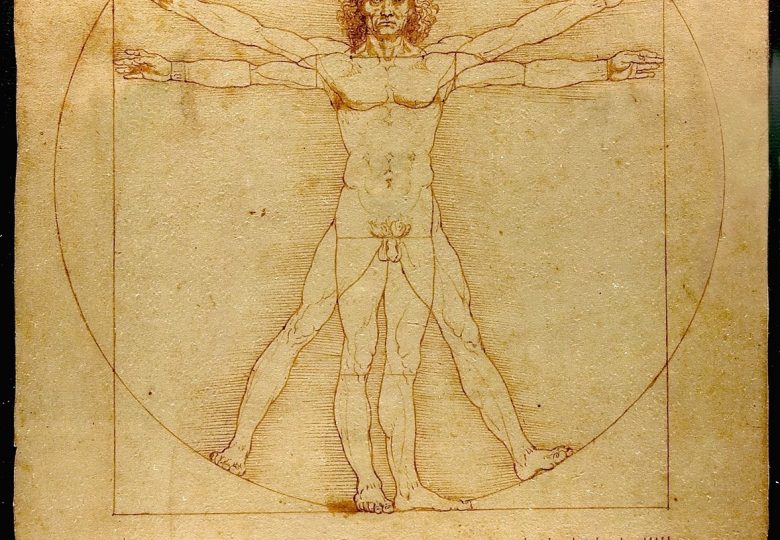

The Renaissance and the Universal Genius

A universal genius is a person who excels in several specialist areas. Only a few people can become universal geniuses, characterized by high intelligence, motivation, curiosity, and inspiration. The term originated in Italy during the Renaissance.

Renaissance ideals

The Renaissance was a cultural movement from the 14th to the 17th century. It originated at the end of the Middle Ages in the Italian peninsula before spreading to the rest of Europe. During the Renaissance, a lord or courtier was expected to be able to speak several languages, play instruments, write poetry, know geography, and travel well.

The word universal genius originally came from the word university. At this time, studying at university often involved an education that spanned several fields, including science, philosophy, theology, riding, fencing, and music. Unlike today’s university studies, which are significantly more specialized, students during the Renaissance received a more specialized apprenticeship only after university studies. University education is highly regarded and very important if you want to become an apprentice in natural science or philosophy. During the Renaissance, Baldassare Castiglione wrote the book Il Cortegiano, which describes how to become a universal genius.

Baldassare Castiglione’s guide emphasized that a universal genius should have many talents, which he called “sprezzatura.” For a courtier, this meant that he should have a detached, relaxed, calm attitude as well as speak well, sing, recite poetry, have good posture, be athletic, know the humanities and classics, be able to paint and draw, and many other skills, without having ostentatious or boastful behavior. The universal genius would perform and display his talents effortlessly, relaxed, and naturally. This gentlemanly ideal is reminiscent of the perfect of Confucius, who long before depicted courtly behavior, righteousness, duty, and willingness to serve as gentlemanly virtues.

The relaxed handling of complex tasks is also reminiscent of corresponding thoughts in Zen, for example, in archery, where conscious attention results in better and more noble skills. Castiglione believes the skills that should appear effortless and achieved without effort should be based on solid knowledge and training. In word and deed, the courtier must: “avoid contrivance and instead…exercise…a certain ‘sprezzatura’ that hides all pretense and makes everything said or done appear spontaneous and without any effort or thought.”

This idea differs somewhat from today’s definition of “universal genius” in that it includes things other than intellectual advancement. Historically (circa 1450–1600), the word referred to a person who strove to “develop his capacity as far as possible”, to combine both mental and physical endowment, and – as Castiglione suggests – to display his talent without “artificiality”. A good athlete also usurps theoretical education, while an educated man would not neglect physical training. For example, Leon Battista Alberti was an architect, artist, poet, sculptor, scientist, mathematician, inventor, and skilled horseman and archer.

Renaissance men

Caution is necessary when interpreting the word universal genius in a source, as it can be interpreted in different ways and has other meanings. All the fields in which the persons were active are often listed in lists of universal geniuses, even though they may have been experts in only one or two fields.

Renaissance ideals today

Renaissance humanism idealized striving to achieve the greatest possible education. During this era, several people came close to perfection with deep knowledge in several fields. Jacob Burckhard established himself in his famous work Renaissance Culture in Italy in 1860. It is considered challenging to gain comprehensive knowledge and even more difficult to be an expert with broad expertise in many areas. The term universal genius is sometimes used with a potentially negative connotation.

Many specialists believe that the ideal of the Renaissance man is doomed to be an anachronism due to today’s hyper-specialization. It is not unusual for a specialist to have accumulated knowledge in a few fields throughout his life, and many experts have become known for their dominance in different subfields or traditions or for their contributions to integrating knowledge of different subfields or traditions.

Today, expertise is often associated with documents, certificates, diplomas, and degrees attributed to such a profession, and a person who appears to have a large amount of these credentials is usually perceived as having more education than practical experience. To create Renaissance ideals, self-taught geniuses usually combine didactic training and expertise in multiple fields with self-taught research and knowledge.